【阿里集团】Timestamp as a Service, not an Oracle.pdf

免费下载

Timestamp as a Ser vice, not an Oracle

Yishuai Li

Alibaba Cloud

Shanghai, China

liyishuai.lys@alibaba-inc.com

Yunfeng Zhu

Alibaba Cloud

Hangzhou, China

yunfeng.zyf@alibaba-inc.com

Chao Shi

Alibaba Cloud

Beijing, China

chao.shi@alibaba-inc.com

Guanhua Zhang

Alibaba Cloud

Hangzhou, China

sengquan.zgh@alibaba-inc.com

Jianzhong Wang

Alibaba Cloud

Hangzhou, China

zelu.wjz@alibaba-inc.com

Xiaolu Zhang

Alibaba Cloud

Beijing, China

xiaoluzhang.zxl@alibaba-inc.com

ABSTRACT

We present a logical timestamping mechanism for ordering transac-

tions in distributed databases, eliminating the single point of failure

(SPoF) that bother existing timestamp “oracles”. The main innova-

tion is a bipartite client–server architecture, where the servers do

not communicate with each other. The result is a highly available

timestamping “service” that guarantees the availability of time-

stamps, unless half the servers are down at the same time.

We study the fundamental needs of timestamping, and formalize

its availability and correctness properties in a distributed setting.

We then introduce the TaaS (timestamp as a service) algorithm,

which denes a monotonic spacetime over multiple server clocks.

We prove, mathematically: (i) Availability that the timestamps are

always computable, provided any majority of the server clocks

being observable; and (ii) Correctness that all the computed time-

stamps must increase monotonically over time, even if some clocks

become unobservable.

We evaluate our algorithm by prototyping TaaS and benchmark-

ing it against state of the art timestamp oracle in TiDB. Our ex-

periment shows that TaaS is indeed immune to SPoF (as we have

proven mathematically), while exhibiting a reasonable performance

at the same order of magnitude with TiDB. We also demonstrate

the stability of our bipartite architecture, by deploying TaaS across

datacenters and showing its resilience to datacenter-level failures.

PVLDB Reference Format:

Yishuai Li, Yunfeng Zhu, Chao Shi, Guanhua Zhang, Jianzhong Wang,

and Xiaolu Zhang. Timestamp as a Service, not an Oracle. PVLDB, 17(5):

994 - 1006, 2024.

doi:10.14778/3641204.3641210

PVLDB Artifact Availability:

The source code, data, and/or other artifacts have been made available at

https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.10467611.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International

License. Visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ to view a copy of

this license. For any use beyond those covered by this license, obtain permission by

emailing info@vldb.org. Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). Publication rights

licensed to the VLDB Endowment.

Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, Vol. 17, No. 5 ISSN 2150-8097.

doi:10.14778/3641204.3641210

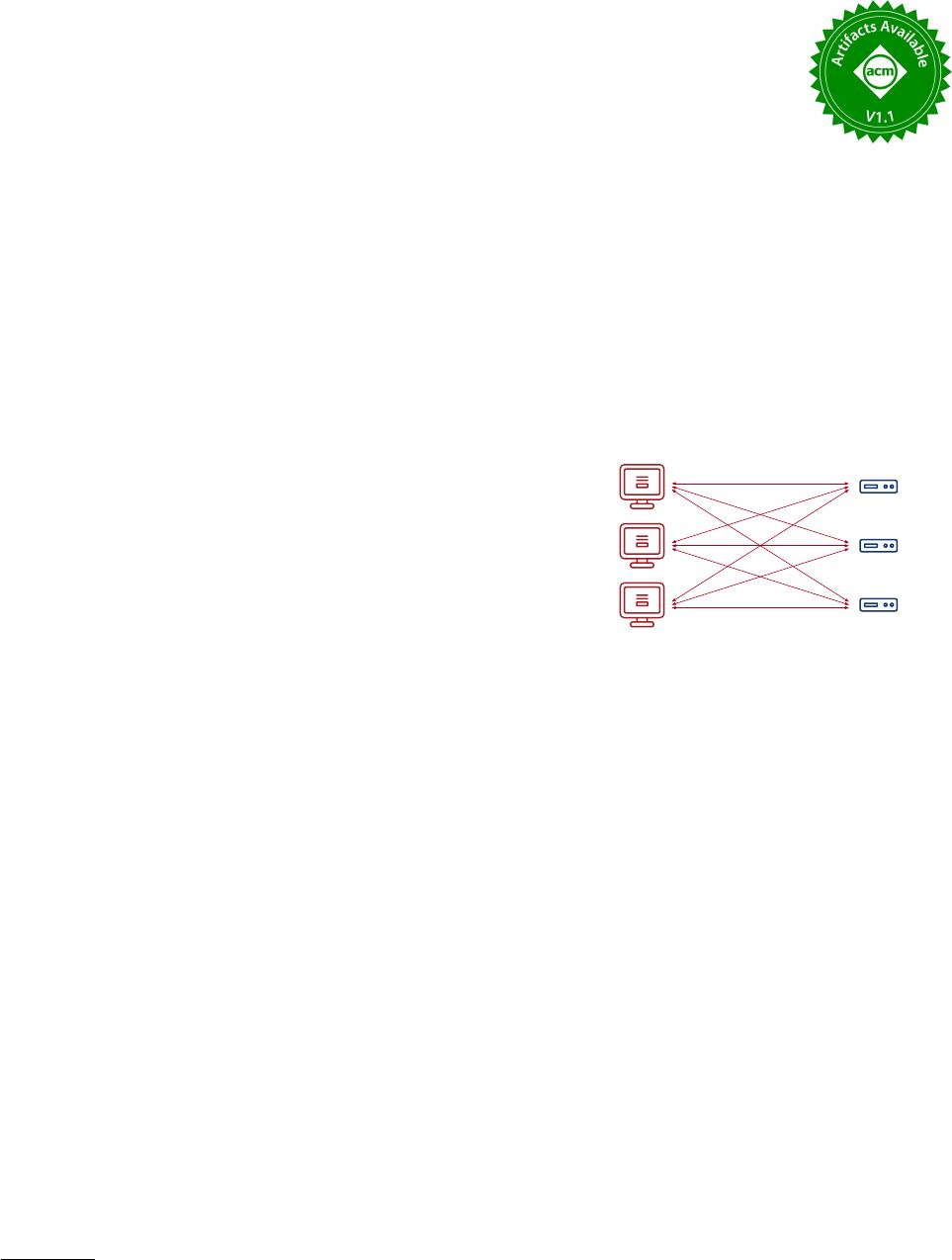

Clients Server

Clocks

tick

Figure 1: Bipartite architecture of TaaS.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Motivation towards a timestamping service

1.1.1 Monotonicity. Distributed databases are concurrent in na-

ture, processing transactions in parallel to exploit scalability. The

transactions should be processed in a correct order, for atomicity,

consistency, and isolation, so called “concurrency control” [12].

To order transactions in a way that meets the users’ intention,

an intuitive way is to timestamp them with logical clocks [

14

],

which extends the precedence relation “

≺

” among transactions into

a consistent total ordering “≤” among timestamps.

1.1.2 Simplicity. The vanilla logical clock by Lamport

[14]

requires

carrying timestamps along every inter-process communication. In

other words, such clocks only capture causality by the “passing of

timestamps”, but not the “owing of time”, making them impractical

for distributed systems, whose participants may communicate via

arbitrary backchannels.

To avoid modifying all the backchannels just for adapting with

logical clocks, industrial systems may deploy a centralized logical

clock that serves as the “wall time”: If transaction

𝜏

1

precedes

𝜏

2

,

then the timestamp assigned for 𝜏

1

is smaller than that of 𝜏

2

.

1.1.3 Availability. The centralizd clock should be fault-tolerant.

For example, PolarDB-X [

3

] backs up its timestamp oracle (TSO)

with a Raft cluster; and OceanBase [

26

] utilizes Paxos. If the leader

clock becomes irresponsive, then the cluster re-elects a new leader

to continue serving timestamps.

However, the leader-based TSO exhibits blackout periods—i.e.,

the cluster cannot serve any timestamp during the re-election pe-

riod, until the new leader takes oce. Such single point of failure

(SPoF) makes the TSO an “oracle”, rather than a “service”.

994

1.2 Contribution

This paper presents Timestamp as a Service (TaaS), a distributed

algorithm that computes logical timestamps from a consensusless

cluster of clocks. The idea is to observe “multiple clocks” simulta-

neosly, rather than focusing on “a distinguished clock”.

As shown in Figure 1, our timestamp service consists of clients

and servers that are bipartite—without client–client or server–

server communications. The server clocks work independently

without synchronizing with each other. The clients compute time-

stamps by ticking multiple server clocks.

The result is a highly availabile timestamping service that is

immune to SPoF: Suppose the cluster consists of

𝑁 =

2

𝑀 −

1 clock

servers, then any

𝑀

servers being “up” (i.e., responsive to client

ticks) guarantees the client to get a timestamp.

In addition to the high availability, the TaaS algorithm also fea-

tures low latency: If all the

𝑁

servers are up, then the client can get

the timestamp within 1RTT (round-trip time) to the farthest server.

If some servers are down or too slow, then the latency is no greater

than 2RTT to the median (i.e., 𝑀-th nearest) server.

This paper is structured as follows: §2 discusses how today’s

databases timestamp transactions and live with the limitations of

“timestamp oracles”. We introduce the TaaS theory in §3, and discuss

how to apply the theory to real-world practices in §4. We prototype

and evaluate the TaaS algorithm in §5, simulating failures of servers

or the entire datacenter. We discuss related and future works in §6,

and conclude in §7.

2 STATE OF THE ART

2.1 Clocks in distributed systems

The concept of timing distributed computations was rst formalized

by Lamport

[14]

, and developed into four avors of clocks that suit

dierent scenarios:

2.1.1 Scalar logical clocks. The original logical clock by Lamport

[14]

linearizes the “happen before” relation

≺

into a total order

≤

or

scalar timestamps, and exhibits completeness when ticked properly:

Denition 1 (Timestamp completeness). A timestamping mecha-

nism is complete if: For all pairs of events where

𝜎

“precedes”

𝜏

, the

timestamp assigned to 𝜎 is less than that assigned to 𝜏:

∀𝜎, ∀𝜏, (𝜎 ≺ 𝜏 =⇒ timestamp of 𝜎 < timestamp of 𝜏)

2.1.2 Vector logical clocks. Mattern

[16]

extends the scalar clocks

into vector clocks that yields a lattice with partial order

<

, achieving

soundness in addition to completeness:

Denition 2 (Timestamp soundness). A timestamping mechanism

is sound if: For all pairs of events

𝜎

and

𝜏

, if the timestamp assigned

to 𝜎 is less than that assigned to 𝜏, then 𝜎 must “precede” 𝜏:

∀𝜎, ∀𝜏, (timestamp of 𝜎 < timestamp of 𝜏 =⇒ 𝜎 ≺ 𝜏)

2.1.3 Hybrid logical clocks (HLC). Kulkarni et al

. [13]

implement

scalar logical clocks with the system’s crystal oscillator, to associate

timestamps with the “time in physical world”. Such physical and

logical timing technique was implemented by CockroachDB [

23

],

MongoDB [

25

], and YugabyteDB [

27

], and enables synchronizing

transactions across databases.

2.1.4 Synchronized clocks. An alternative to “synchronizing dif-

ferent clocks” is to deploy “one clock that synchronizes all”, either

physically or logically:

TrueTime. Spanner [

4

] timestamps transactions by the TrueTime

API, where the “timeslave daemon” polls multiple “time masters”

equipped with GPS receivers and atomic clocks. The result is a

highly accurate timer with uncertainties less than 10 milliseconds.

Centralized timestamping. To avoid the cost of atomic clocks

(which aren’t cheap enough as of 2023), serveral databases generate

timestamps from a centralized “timestamp oracle”, e.g., CORFU

sequencer [

2

], PolarDB-X TSO [

3

], TiDB placement driver [

10

],

Percolator TSO [

19

], Postgres-XL global transaction manager [

20

],

Omid TO [21], and OceanBase global timestamp service [26].

Centralized timestamping drops the dependency on highly-precise

hardware clocks. The lightweight and simple design makes it popu-

lar among databases deployed within the same datacenter, or across

co-located datacenters—where the round-trip overhead for fetching

timestamps does not signicantly aect the performance.

Scope. This paper focuses on centralized timestamping. We are

especially concerned about the availability of the timestamp “ora-

cles”, which we further discuss in §2.2.

2.2 Availability of timestamp oracles

As its name suggests, the “centralized” timestamp oracle plays a

critical part in the database system: If the oracle is down, then no-

body can propose any transactions. Therefore, all timestamp oracles

to our knowledge are backed up with a failover cluster organized

by consensus—more specically, leader-based consensus such as

Multi-Paxos [15] and Raft [18]—and thus inherit their drawbacks.

2.2.1 Leader, single point of failure. Leader-based timestamp ora-

cles are bottlenecked in both availability and performance:

(1)

When the leader crashes or hangs, all existing timestamp ora-

cles stop service, until the cluster re-elects a new leader that

continues to serve timestamps. Such blackout period can be

tuned with consensus algorithm parameters, but never elimi-

nated in a leader-based setting.

(2)

The latency of fetching timestamps depends on the network

connection between the client and the leader. If the leader’s

network stack is overloaded, then the clients might immediately

experience downgraded performance.

Goal 1. We want to eliminate the bottleneck, and provide a lead-

erless timestamping service that is resistant to single-point failures.

2.2.2 Performance vs Completeness vs Availability. Apart from the

SPoF issue, timestamp oracles face another problem that: Given

a leader-based consensus, how to request timestamps from it?

(i) “Write through” all timestamps to the quorum, or (ii) Use the

leader as a “write back” cache?

“Writing through” bases completeness on the consistency of

consensus. The leader propagates every requested timestamp to

its followers. Upon re-election, the new leader serves on top of the

previously issued timestamp, and thus guarantees completeness.

To reduce the performance overhead of propagating each request,

real-world oracles choose the write-back approach (ii), where the

995

of 13

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论