D-Bot Database Diagnosis System using Large Language Models.pdf

免费下载

D-Bot: Database Diagnosis System using Large Language Models

Xuanhe Zhou

1

, Guoliang Li

1

, Zhaoyan Sun

1

, Zhiyuan Liu

1

, Weize Chen

1

, Jianming Wu

1

Jiesi Liu

1

, Ruohang Feng

2

, Guoyang Zeng

3

1

Tsinghua University

2

Pigsty

3

ModelBest

zhouxuan19@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn,liguoliang@tsinghua.edu.cn

ABSTRACT

Database administrators (DBAs) play an important role in manag-

ing, maintaining and optimizing database systems. However, it is

hard and tedious for DBAs to manage a large number of databases

and give timely response (waiting for hours is intolerable in many

online cases). In addition, existing empirical methods only support

limited diagnosis scenarios, which are also labor-intensive to update

the diagnosis rules for database version updates. Recently large

language models (LLMs) have shown great potential in various

elds. Thus, we propose D-Bot, an LLM-based database diagnosis

system that can automatically acquire knowledge from diagnosis

documents, and generate reasonable and well-founded diagnosis

report (i.e., identifying the root causes and solutions) within ac-

ceptable time (e.g., under 10 minutes compared to hours by a DBA).

The techniques in D-Bot include

(𝑖)

oine knowledge extraction

from documents,

(𝑖𝑖)

automatic prompt generation (e.g., knowledge

matching, tool retrieval),

(𝑖𝑖𝑖)

root cause analysis using tree search

algorithm, and

(𝑖𝑣)

collaborative mechanism for complex anom-

alies with multiple root causes. We verify D-Bot on real benchmarks

(including 539 anomalies of six typical applications), and the results

show that D-Bot can eectively analyze the root causes of unseen

anomalies and signicantly outperforms traditional methods and

vanilla models like GPT-4.

PVLDB Artifact Availability:

The source code, data, technical report, and other artifacts have been made

available at https://github.com/TsinghuaDatabaseGroup/DB-GPT.

1 INTRODUCTION

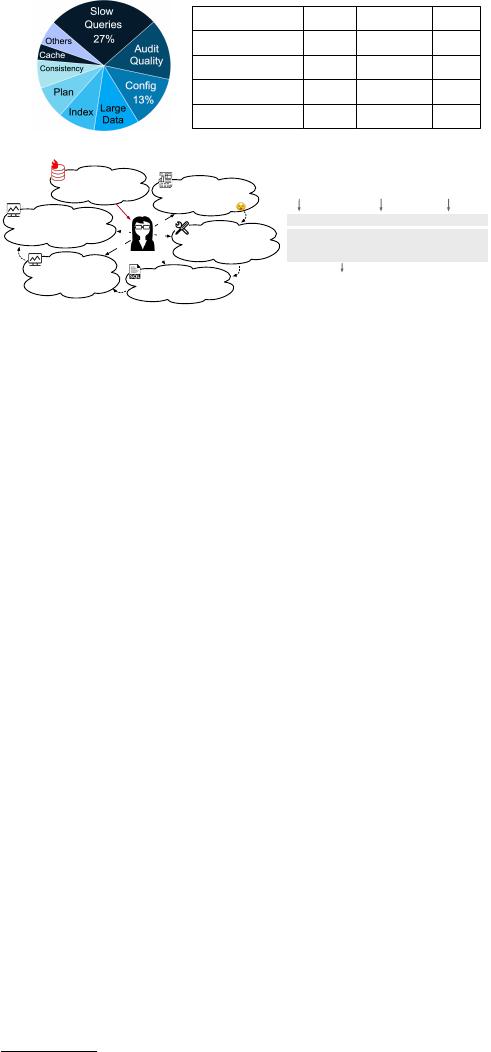

Database diagnosis aims to detect, analyze, and resolve anomaly

events in database systems, thereby ensuring high data availability

and workload performance. However, database anomalies are re-

markably diverse, making it impossible to comprehensively cover

them with predened rules [

18

]. As shown in Figure 1 (a), a data-

base vendor encountered over 900 anomaly events in three months,

most of which spanned various facets of database and system mod-

ules (e.g., slow query processing, locking mechanisms, improper

congurations). Furthermore, these modules exhibit complex cor-

relations with system metrics (e.g., high CPU usage may result

from concurrent commits or massive calculations). So it requires to

explore dierent reasoning strategies (e.g., investigating dierent

system views) before identifying the potential root causes.

As a result, database diagnosis is a challenging problem, where

“the devil is in the details” [

11

,

62

]. Many companies rely on the

expertise of human database administrators (DBAs) to undertake

diagnosis tasks. Here we present a simplied example (Figure 1 (c)):

(1) Anomaly Notication. The database user noties an anomaly,

e.g., “routine queries

...

is 120% slower than the norm

...

”; (2) Alert

Detection. Upon receiving the user’s notication, the DBA rst

[CpuHigh alert] was

triggered, and so I need

to retrieve 5 metrics …

One query took up

60% cpu time. It may

be the bottleneck!

Ok, I cannot find

any more causes. Let’s

write the report

2.

3.

1.

4.

5.

(c) Diagnosis by Human

(a) Anomaly Events (b) Comparison of Diagnosis Methods

Routine workload

gets extremely slow …

Great! I find the query

can be optimized by

adding one index …

!

Classifier

(E.g., Decision Tree, MLP, RNN)

(d) Classifier for Fixed Scenario

Fixed Numeric Metrics

inactive_memory

process_blocked

process_running

Selected Label

(Missing Index)

Fixed

Labeles

…

High

Generalizability

Low

High

High

Low

D-Bot

Most

Low

High

Classifier

Metric-Based

Low

Most

High

Human

Efficiency

Expense

Supported Anomaly

Criteria \ Method

123

1

1469304832

Normalization

From the 5 CPU

metrics, I find some

abnormal events ..,

Figure 1: Database diagnosis is a complex problem mainly

handled by human expertise – (a) example root causes of

anomalies in a database vendor; (b) comparison of diagnosis

methods; (c) toy example of diagnosing by human DBA; (d)

example of diagnosing by machine learning classier.

investigates the triggered alerts. For instance, the DBA discovers

a “CPU High” alert, indicating the total CPU usage exceeded 90%

for 2 minutes; (3) Metric Analysis. Next the DBA delves deeper to

explore more CPU-related metrics (e.g., the number of running

or blocked processes, the number of query calls). By analyzing

these metrics, the DBA concludes the issue was caused by some

resource-intensive queries. (4) Event Analysis. The DBA retrieves

the statistics of top-k slow queries (query templates) from database

views, and nds one query consumed nearly 60% of the CPU time.

(5) Optimization Advice. The DBA tries to optimize the problematic

query (e.g., index update, SQL rewrite) by experience or tools.

The above diagnosis process is inherently iterative (e.g., if the

DBA fails to nd any abnormal queries, she may turn to investigate

I/O metrics). Besides, the DBA needs to write a diagnosis report

1

to facilitate the user’s understanding, which includes information

like root causes together with the detailed diagnosis processes.

However, there exists a signicant gap between the limited ca-

pabilities of human DBAs and the daunting diagnosis issues. Firstly,

training a human DBA demands an extensive amount of time, often

ranging from months to years, by understanding a large scale of

relevant documents (e.g., database tuning guides) and the necessity

for hands-on practice. Secondly, it is nearly impossible to employ

sucient number of human DBAs to manage a vast array of data-

base instances (e.g. millions of instances on the cloud). Thirdly, a

human DBA may not provide timely responses in urgent scenar-

ios, especially when dealing with correlated issues across multiple

1

Over 100 diagnosis reports are available on the website http://dbgpt.dbmind.cn/.

database modules, which potentially lead to signicant nancial

losses. Thus, if typical anomalies can be automatically resolved, it

will relieve the burden of human DBAs and save resources.

Driven by this motivation, many database products are equipped

with semi-automatic diagnosis tools [

20

,

22

,

29

,

30

,

32

]. However,

they have several limitations. First, they are built by empirical

rules [

11

,

62

] or small-scale ML models (e.g., classiers [

34

]), which

have poor scenario understanding capability and cannot utilize the

diagnosis knowledge. Second, they cannot be exibly generalized to

scenario changes. For empirical methods, it is tedious to manually

update and verify rules by newest versions of documents. And

learned methods (e.g., XGBoost [

8

], KNN [

17

]) require to redesign

the input metrics and labels, and retrain models for a new scenario

(Figure 1 (d)). Third, these methods have no inference ability as

human DBAs, such as recursively exploring system views based on

the initial analysis results to infer the root cause.

To this end, we aim to build an intelligent diagnosis system with

three main advantages [

65

]. (1) Precise Diagnosis. First, our sys-

tem can utilize tools to gather scenario information (e.g., query

analysis with ame graph) or derive optimization advice (e.g., index

selection), which are necessary for real-world diagnosis. However,

that is hardly supported by traditional methods. Second, it can

conduct basic logical reasoning (i.e., making diagnosis plans). (2)

Expense and Time Saving. The system can relieve human DBAs

from on-call duties to some extent (e.g., resolving typical anom-

alies that rules cannot support). (3) High Generalizability. The

system exhibits exibility in analyzing unseen anomalies based on

both the given documents (e.g., new metrics, views, logs) and past

experience.

Recent advances in Large Language Models (LLMs) oer the

potential to achieve this goal, which have demonstrated superiority

in natural language understanding and programming [

42

,

43

,

64

,

67

].

However, database diagnosis requires extensive domain-specic

skills and even the GPT-4 model cannot directly master the diagnosis

knowledge (lower than 50% accuracy). This poses three challenges.

(C1) How to enhance LLM’s understanding of the diagno-

sis problem? Despite pre-trained on extensive corpora, LLMs still

struggle in eectively diagnosing without proper prompting

2

(e.g.,

unaware of the database knowledge). The challenges include

(𝑖)

extracting useful knowledge from long documents (e.g., correla-

tions across chapters);

(𝑖𝑖)

matching with suitable knowledge by

the given context (e.g., detecting an alert of high node load);

(𝑖𝑖𝑖)

retrieving tools that are potentially useful (e.g., database catalogs).

(C2) How to improve LLM’s diagnosis performance for single-

cause anomalies? With knowledge-and-tool prompt, LLM needs

to judiciously reason about the given anomalies. First, dierent from

many LLM tasks [

12

], database diagnosis is an interactive procedure

that generally requires to analyze for many times, while LLM has

the early stop problem [

13

]. Second, LLM has a “hallucination”

problem [

46

], and it is critical to design strategies that guide LLM

to derive in-depth and reasonable analysis.

(C3) How to enhance LLM’s diagnosis capability for multi-

cause anomalies? From our observation, within time budget, a

single LLM is hard to accurately analyze for complex anomalies

2

Prompting is to add additional information into LLM input. Although LLMs can mem-

orize new knowledge with ne-tuning, it may forget previous knowledge or generate

inaccurate or mixed-up responses, which is unacceptable in database diagnosis.

(e.g., with multiple root causes and the critical metrics are in ner-

granularity). Therefore, it is vital to design an ecient diagnosis

mechanism where multiple LLMs can collaboratively tackle com-

plex database problems (e.g., with cross reviews) and improve both

the diagnosis accuracy and eciency.

To tackle above challenges, we propose D-Bot, a database diag-

nosis system using large language models. First, we extract useful

knowledge chunks from documents (summary-tree based knowl-

edge extraction) and construct a hierarchy of tools with detailed

usage instructions, based on which we initialize the prompt tem-

plate for LLM diagnosis (see Figure 3). Second, according to the

prompt template, we generate new prompt by matching with most

relevant knowledge (key metric searching) and tools (ne-tuned

SentenceBert), which LLM can utilize to acquire monitoring and

optimization results for reasonable diagnosis. Third, we introduce a

tree-based search strategy that guides the LLM to reect over past

diagnosis attempts and choose the most promising one, which sig-

nicantly improves the diagnosis performance. Lastly, for complex

anomalies (e.g., with multiple root causes), we propose a collabora-

tive diagnosis mechanism where multiple LLM experts can diagnose

in an asynchronous style (e.g., sharing analysis results, conducting

cross reviews) to resolve the given anomaly.

Contributions. We make the following contributions.

(1) We design an LLM-based database diagnosis framework to

achieve precise diagnosis (see Section 3).

(2) We propose a context-aware diagnosis prompting method that

empowers LLM to perform diagnosis by

(𝑖)

matching with relevant

knowledge extracted from documents and

(𝑖𝑖)

retrieving tools with

a ne-tuned embedding model (see Sections 4 and 5).

(3) We propose a root cause analysis method that improves the di-

agnosis performance using tree-search-based algorithm that guides

LLM to conduct multi-step analysis (see Section 6).

(4) We propose a collaborative diagnosis mechanism to improve the

diagnosis eciency, which involves multiple LLMs concurrently

analyzing issues by their domain knowledge (see Section 7).

(5) Our experimental results demonstrate that D-Bot can accurately

identify typical root causes within acceptable time (see Section 8).

2 PRELIMINARIES

2.1 Database Performance Anomalies

R1.D2

Database Performance Anomalies refer to the irregular or unex-

pected issues that prevent the database from meeting user perfor-

mance expectations [

35

,

45

], such as excessively high response time.

Figure 2 show four typical database performance anomalies

3

.

(1) Slow Query Execution. The database experiences longer re-

sponse time than expectancy. For example, the slow query causes

signicant increase in CPU usage (system load) and query duration

time, but the number of active processes remains low.

(2) Full Resource Usage. Some system resource is exhausted, pre-

venting it accepting new requests or even causing errors (e.g., insert

failures for running out of memory). For example, the high concur-

rency workload can not only cause great CPU and memory usage,

but signicantly increases the number of active processes.

3

Anomalies on the application/network sides and non-maintenance issues like database

kernel debugging and instance deployment fall outside the scope of this work.

2

of 15

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论