SIGMOD2014_Matching heterogeneous event data_Xiaochen Zhu, Shaoxu Song, Xiang Lian, Jianmin Wang, Lei Zou.pdf

免费下载

Matching Heterogeneous Event Data

Xiaochen Zhu

§

Shaoxu Song

§

Xiang Lian

†

Jianmin Wang

§

Lei Zou

‡

§

KLiss, MoE; TNList; School of Software, Tsinghua University, China

zhu-xc10@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn {sxsong, jimwang}@tsinghua.edu.cn

†

University of Texas - Pan American, USA lianx@utpa.edu

‡

Peking University, China zoulei@pku.edu.cn

ABSTRACT

Identifying duplicate events are essential to various business

process applications such as provenance querying or process

mining. Distinct features of heterogeneous events includ-

ing opaque names, dislocated traces and composite events,

prevent existing data integration from techniques perform-

ing well. To address these issues, in this paper, we propose

an event similarity function by iteratively evaluating similar

neighbors. We prove the convergence of iterative similarity

computation, and propose several pruning and estimation

methods. To efficiently support matching composite events,

we devise upper bounds of event similarities. Experiments

on real and synthetic datasets demonstrate that the pro-

posed event matching approaches can achieve significantly

higher accuracy than the state-of-the-art matching methods.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

H.2.5 [Database Management]: Heterogeneous Databases

Keywords

Schema matching; event matching

1. INTRODUCTION

Owing to various mergers and acquisitions, information

systems (e.g., Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) and Of-

fice Automation (OA) systems), probably developed inde-

pendently in different branches or subsidiaries in large-scale

corporations, keep on generating heterogeneous event logs.

We surveyed a major bus manufacturer who recently started

a project on integrating their event data in the OA systems

of 31 subsidiaries. These OA systems have been built inde-

pendently on 5 distinct middleware products in the past 20

years. More than 8190 business processes are implemented

in these systems, among which 68.8% are indeed different

implementations of the same business activities in different

subsidiaries. For instance, in the following Example 1, we

illustrate two versions of turbine order processing processes

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full cita-

tion on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than

ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or re-

publish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission

and/or a fee. Request permissions from Permissions@acm.org.

SIGMOD’14, June 22–27, 2014, Snowbird, UT, USA.

Copyright 2014 ACM 978-1-4503-2376-5/14/06 ...$15.00.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2588555.2588570.

in 31 subsidiaries. Duplicate events commonly exist in these

heterogeneous processes for the same business activities.

The company has started to integrate these heterogeneous

event data into a unified business process data warehouse

[3, 4], where different types of analyses can be performed,

e.g., querying similar complex procedures or discovering in-

teresting event patterns in different subsidiaries (complex

event processing, CEP [6]), comparing business processes

in different subsidiaries to find common parts for process

simplification and reuse [19], or obtaining a more abstract

global picture of business processes (workflow views [2]) in

the company. Without exploring the correspondence among

heterogeneous events, applications such as query and analy-

sis over the event data may not yield any meaningful results.

The event matching problem is to construct the similar-

ity and matching relationship of events from heterogeneous

sources. Although there are 49 system integrators (subject-

matter experts) employed by the bus manufacturer in the

project of OA system integration, given the large number

of more than 100,000 event activities, manually checking

the correspondences of all possible event pairs is highly im-

practical for two reasons: 1) manual checking is obviously

inefficient, and 2) manual checking results could be inaccu-

rate and contradictory. An automatic approach is highly

demanded for matching these heterogeneous event data.

Different from conventional schema matching on attributes

in relational databases [7], there are strong relationships of

consecutive occurrence among events. The event data in-

tegration is challenging due to the following features com-

monly observed in the general event data.

(1) Event names could be opaque, due to various encoding,

syntax or language conventions in heterogeneous systems.

(2) Event traces might be dislocated. Only a part (e.g., the

beginning) of a trace 1 corresponds to a distinct part (e.g.,

the end) of another trace 2.

(3) Composite event may exist. That is, one event in a

source corresponds to several decomposed ones in another

source, known as composite event in CEP [6].

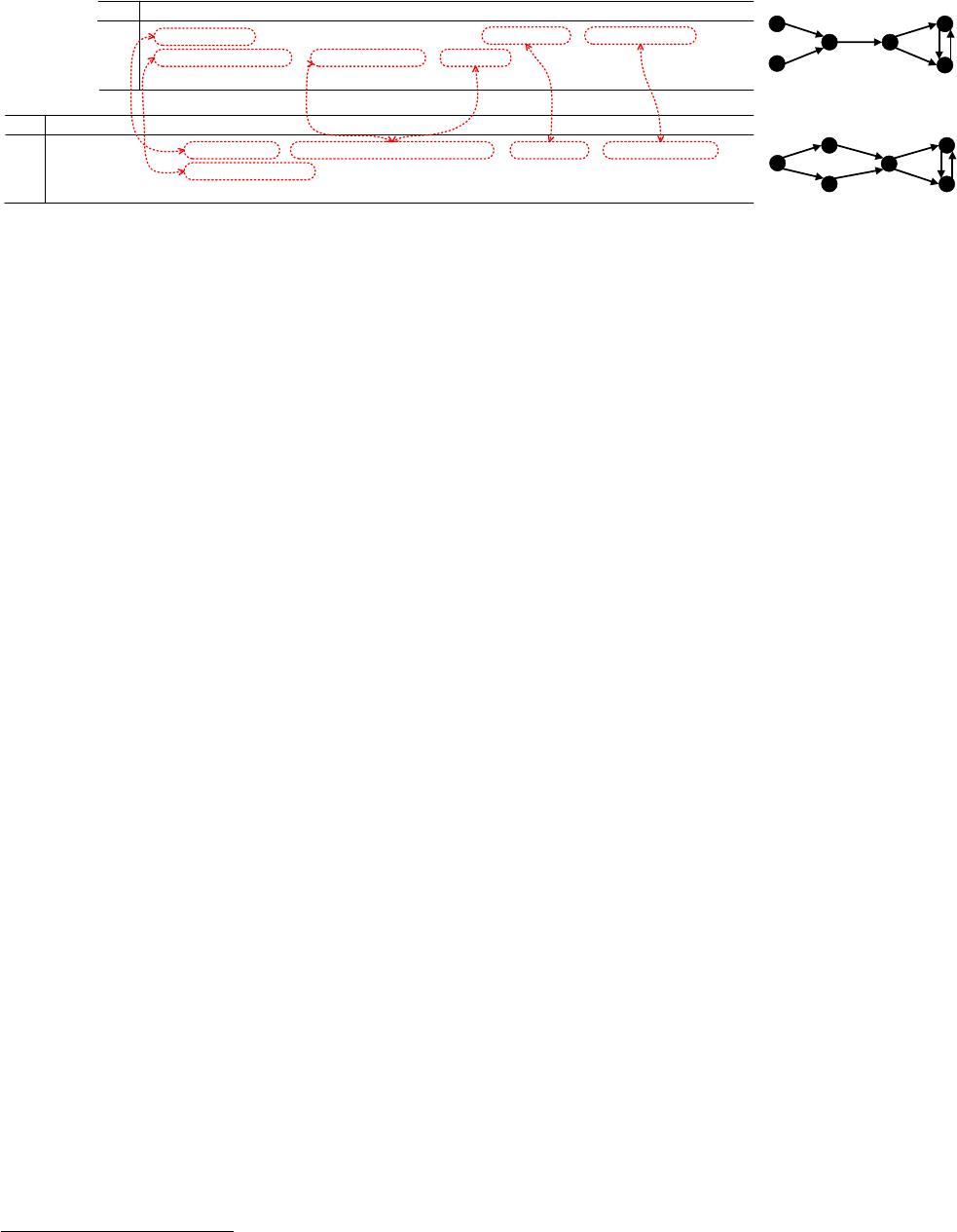

Example 1. Figure 1 illustrates two fragments of event logs

L

1

and L

2

for turbine order processing in two different sub-

sidiaries of the bus manufacturer, respectively. Two exam-

ple traces are shown in each fragment, and each trace de-

notes a sequence of events (steps) for processing one order.

An event log consists of many traces, among which the se-

quences of events may be different, since some of the events

can be executed concurrently (e.g. Ship Goods(E) and Email

1211

ID

Trace

t1

t2

Paid by Cash (A) Check Inventory (C) Validate (D) Ship Goods (E) Email Customer (F)

Paid by Credit Card (B) Check Inventory (C) Validate (D) Email Customer (F) Ship Goods (E)

...

ID

Trace

s1

s2

Order Accepted (1) Paid by Cash (2) Inventory Checking & Validation (4) ????????? (5) Send Notification (6)

Order Accepted (1) Paid by Credit Card (3) Inventory Checking & Validation (4) Send Notification (6) ???????? (5)

...

B

C

A

D

E

F

1

2

3

4

5

6

(a) Event log L

1

(b) Event log L

2

(c) Dependency Graph G

1

of

L

1

(d) Dependency Graph G

2

of

L

2

0.4

0.6

0.4

0.6

0.4

0.6

0.6

0.4

0.4

0.60.6

0.6

0.4

0.4

1.0

Figure 1: Fragments of two event logs and their dependency graphs

Customer(F) in L

1

), or exclusively (e.g., Paid by Cash(2) or

Paid by Credit Card(3) in L

2

).

Note that opaque names exist in L

2

as shown in Figure

1(b). The event “????????(5)” is collected from a database

whose encoding is distinct from others, which makes the

event name garbled. According to expert investigation, the

original name of “????????(5)” should be “Delivery(5)”, and

the true event corresponding relation between L

1

and L

2

is

highlighted by red dashed lines in Figures 1(a) and (b).

Dislocated matching exists between the first traces in L

1

and L

2

. Event Paid by Cash(A) that appears at the beginning

of traces in L

1

corresponds to event Paid by Cash(2), which

appears in the middle of traces in L

2

, having another event

Order Accepted(1) before it.

Moreover, two events Check Inventory(C) and Validate(D)

in L

1

correspond to one composite event Inventory Checking

& Validation(4). For simplicity, we use ABCDEF to denote

event names in L

1

, while 123456 are events in L

2

.

Unfortunately, existing techniques cannot effectively ad-

dress the aforesaid three challenges in event matching. A

straightforward idea of matching events is to compare their

names (a.k.a. event labels). String edit distance (syntactic

similarity) [13] as well as word stemming and the synonym

relation (semantic similarity) [20] are widely used in the la-

bel similarity based approaches [14, 19, 5, 23]. As shown in

Example 1, such a typographical similarity cannot address

the identified Challenge 1, i.e., opaque event labels.

Structural similarity may be considered besides the typo-

graphical similarity. The idea is to construct a graph for de-

scribing the relationships among events, e.g., the frequency

of appearing consecutively in an event log [8]. Once the

graphical structure is obtained, graph matching techniques

can be employed to identify the event (behavioral/structural)

similarities. Unfortunately, existing graph matching tech-

niques cannot handle well the dislocated matching of events

1

,

i.e., the aforesaid Challenge 2. Graph edit distance (GED)

[5] for general graph data and normal distance for matching

with opaque names (OPQ) [11] concern a local evaluation

of similar neighbors. However, as illustrated in Example 1,

dislocated matching events may have distinct neighbors (see

more details below). Rather than local neighbors, another

type of Simrank [10] like behavioral similarity (BHV) [19]

considers a global evaluation via propagating similarities

in the entire graph in multiple iterations. Unfortunately,

directly applying the global propagation does not help in

1

According to our survey on 5642 processes with redundancy

(68.8% of 8190) of the bus manufacturer, more than 44% of

them involve dislocated event traces.

matching dislocated events that do not have any predeces-

sor, e.g., Paid by Cash(A) in Figure 1.

Example 2. Figures 1(c) and 1(d) capture the statistical

and structural information of L

1

and L

2

, respectively (see

Definition 1 for constructing G

1

and G

2

). Each vertex in the

directed graph denotes an event, while an edge between two

events (say AC in Figure 1(c) for instance) indicates that

they appear consecutively in at least one trace (e.g., trace 1

in Figure 1(a)). The numbers attached to edges represent

the normalized frequencies of consecutive event pairs. For

instance, 0.4 of AC means that A,C appear consecutively in

40% of the traces of the event log.

Since GED and OPQ concern more about the local simi-

larity, e.g., the high similarity of (A, C) and (1, 2), an event

mapping M = {A → 1, B → 3, C → 2, D → 4, E → 5, F →

6} will be returned by GED with distance 0.16 and OPQ

with score 10.7. The true mapping M

0

= {A → 2, B →

3, C/D → 4, E → 5, F → 6} in ground truth shows a higher

GED distance 0.233 (lower is better) and lower OPQ score

10 (higher is better) instead. BHV does not help in capturing

dislocated mapping, e.g., between A and 2 with BHV similar-

ity 0. Instead, A and 1 with no input neighbors have higher

similarity 1, i.e., unable to find the dislocated matching.

When matching composite events, i.e., Challenge (3), com-

puting efficiency becomes a major issue. For instance, one

may be interested in composite events {C, D}, {D, E} and

{E, F } in Figure 1(c). Given a candidate set of n composite

events, there may exist 2

n

possible combinations, for each

of which we need to evaluate the corresponding event simi-

larities. Unfortunately, structural similarities such as GED

are already costly to compute for one combination.

Contributions. In this paper, we propose a similarity func-

tion that supports dislocated matching and opaque events,

by iteratively computing neighbor similarities. Our major

contributions in this paper are summarized as follows.

(1) We formally define the similarity function, which is it-

eratively computed by incorporating other similarity crite-

ria in the iteration. Intuitively, as discussed in Example 2,

directly applying OPQ that concerns a local evaluation of

similar neighbors is ineffective in matching dislocated events

with possibly distinct neighbors. In contrast, the proposed

iteration based similarity function concerns the global eval-

uation via propagating similarities, and thus overcomes the

impact of local neighbor distinctness.

(2) We prove the convergence of the proposed iteration

based similarity function and devise a pruning technique

1212

of 12

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论